Elixir, Phoenix and the challanges of the new web

08 Nov 2019

Erlang

Elixir is a dynamic programming language, designed to develop scalable and maintainable applications. Elixir runs on top of the Erlang virtual machine.

This virtual machine was created by Ericcson to solve telephony problems. Specifically switching equipment, which are necessary for the operation of telephone calls.

They had requirements for high concurrency, high availability, fault tolerance, low latency and support for distributed programming.

As it was very difficult for them to program in the languages they were used to, they decided to create their own language. And so Erlang was born.

Concurrency is a difficult problem. Some languages do not have good support for concurrency and others use different strategies to address this problem.

The way they implemented concurrency in Erlang was through light processes.

These processes are not threads of the operating system, but they are processes handled by the Erlang virtual machine.

These processes work in isolation and communicate with each other through messages.

And they are very light. So light, that in the same computer there can be hundreds of thousands of live processes at the same time.

On computers with multiple cores, these processes can run in parallel.

If we have a computer with 32 cores, and we have 32 processes, it is possible that at any given time each process runs on a different core.

The Erlang virtual machine can take full advantage of the computers capacity.

And that is important, because every year computers come with more cores.

Elixir

In 2010, José Valim was working on improving the speed of Rails in multi-core systems, since the machines he used in production had more cores every year.

As he says, the whole experience was very frustrating. Rails did not provide the appropriate tools to solve concurrency problems. That’s when José started looking at other technologies and eventually ran into the Erlang Virtual Machine.

José started using Erlang, and realized that Erlang was an ideal base for solving the problems he wanted to solve. But he also noticed that he missed some constructions that were present in other languages.

So, he decided to create Elixir.

A look at Elixir

The first thing they will notice when the syntax looks a lot like Ruby’s.

defmodule Math do

# Esto es un comentario

def sum(a, b) do

a + b

end

end

Math.sum(1,2) #=> 3

1 # There are numbers,

true # there are booleans,

"Hola" # there are strings,

:chau # there are symbols (in elixir they are called atoms),

[1,2,3] # there are arrays (in elixir they are called lists or tuples),

%{key: "value"} # there are hashes (in elixir they are called maps),

1..5 # there are rangs

Plus

- as in Ruby, there is no need to put semicolons at the end of each line,

- as in Ruby, every expression returns a value,

- as in Ruby, the last expression is what returns the function (no need to use return )

There are many similar constructions, and this is because José Valim relied heavily on Ruby’s syntax.

If you like Ruby for being an expressive, elegant, flexible, simple, easy to read and understand languages, and that allows you to do a lot with little code, then for the same reasons you will love Elixir.

But Elixir looks more like Erlang than Ruby.

Elixir is not an Object Oriented language. There are no classes, there is no inheritance, there is no new or initialize , there are no instance variables, there are no global variables, there are no objects. There is no mutable state.

And this is not a whim.

Erlang was designed with concurrency in mind, and it is very difficult to implement concurrency when we have a mutable state distributed throughout our application.

The mutable state is one that changes over time. Time is a source of complexity, because it adds many moving parts to our system. We end up with several pieces of data changing at different intervals.

That is why if we are designing a concurrent language, we do not want the mutable state to be a primitive in that language, but an abstraction to which we turn when we need it.

In Ruby, objects conflate

- data representation

- program logic

- code organization

- status management and

- polymorphism (by inheritance).

In Elixir all these concerns are separately addressed.

For example, let’s compare the following codes in Ruby and Elixir:

# Ruby

"HOLA".downcase #=> "hola"

# Elixir

String.downcase("HOLA") #=> "hola"

In Ruby, "HOLA" is an object of class String, which defines the method downcase. The object "HOLA" knows how to get lowercase. We say that data representation is coupled to program logic.

In Elixir, on the other hand, we separate the data representation (the string “Hello”) from the program logic (The String.downcase function).

The string "HOLA" is not an object. Is a value. And the values have no behavior.

- They don’t know how to lowercase themselves.

- They do not know how to calculate their length.

- They don’t know how to concatenate with another value.

They do not carry anything but themselves. They do not have a pointer to their methods or their class, or their ancestors, or instance variables.

In Elixir the values are simple. They are easy to create and easy to share.

Identity

What does the following expression return to us?

# Ruby

"Hola".equal?("Hola")

It returns us false.

# Ruby

a = "Hola"

b = "Hola"

a.object_id #=> 70227497266080

b.object_id #=> 70227497236260

The strings in the example have different object_id. They are different objects.

As much as both are made up of the same letters in the same order, we cannot say that they are the same string. They are objects stored in different memory locations.

In Elixir, however, there is no concept of equal?, because there is no concept of object_id.

# Elixir

"Hola" == "Hola" #=> true

If two strings have the same letters in the same order, we say they are the same value. The identity of a value is given by the value itself. We say that the values in Elixir are identifiable by themselves.

"Hola" is not a box where I keep a value. Nor is it a pointer to a value. "Hola" is the value in itself.

And this also applies to data structures.

# Elixir

[1, 2, 3] == [1, 2, 3] #=> true

If we have the list [1, 2, 3] on our computer, and the list [1, 2, 3] on a computer in China, we say they are the same list.

What defines a value is not its position in memory.

In elixir we abstract from memory. And this is not a whim either. If we do not have pointers and we have values by reference we do not need to protect a portion of memory with locks, traffic lights or monitors. That makes it easier to implement concurrent systems.

Immutable values

And as a consequence the values are immutable. The values are never modified.

In Ruby I can instantiate an object, call a destructive method and modify the original object:

# Ruby

a = "HOLA"

a.downcase! #=> "nil"

a #=> "hola"

In Elixir instead, the values cannot be modified. When I call the downcase function, I pass a value per parameter and the function does not modify it, but returns a new value:

# Elixir

a = "HOLA"

String.downcase(a) #=> "hola"

a #=> "HOLA"

If the data is immutable, then the problems of interaction between processes by data mutation are eliminated. This makes it much easier to implement a concurrent system.

Functions

In Elixir, function parameters are passed by value, not by reference, and this makes it easy to implement pure functions.

A pure function is one in which the values it returns depend solely on the input parameters. Given the same parameters, a pure function always returns the same result.

If a function depends only on its input parameters it is much easier to predict its behavior. And it is much easier to test it. And it is much easier to reason about the function. If the functions are pure, it is easier to implement a concurrent system.

In Ruby we pass the parameters by reference. We make it possible for a method to modify the original object outside the function call. And the methods have access to the internal state of the object. Instance variables can be accessed and modified by methods.

In Ruby, it can happen that we have a bug that only happens when an object is in a particular state.

Reproducing the problem can be complicated because it is not always easy to decipher the internal state of an object. And once it is done it can be difficult to reproduce it, because perhaps it only happens after a particular chain of events activates it.

In functional programming, the data is passed through a set of functions and the data never changes. The output of a function is the input of the following function. When an error occurs it is easier to decipher what happens and where it happens. The mutation means loss of information, and there is no mutation in Elixir.

Which does not mean there are no side effects. Eventually we will want to write something on the screen, or access a database or a server. Or create a process. And all that can be done perfectly in Elixir.

Processes

# Elixir

spawn(fn -> 1 + 2 end)

#=> #PID<0.111.0>

The spawn function is the most basic function to create processes. What it returns is the PID, which is the unique process identifier. Processes are created, they do what they have to do and die.

There are functions to create them, there are functions to send and receive messages, there are functions to link processes to each other.

But in real life, we never call spawn directly, but we go to abstractions.

- If we want to implement a producer / consumer model, we will use GenStage.

- If we want to implement a simple task, we will use Task.

- If we want to implement a client / server model, we will use Agentor GenServer.

- If we want one process to supervise another, we will use Supervisor.

And if a process fails, the supervisor process can revive it in a safe state. In elixir we can create supervisor trees, which give the application fault tolerance and allow self-healing. There are Erlang applications that have been running non-stop for 20 years.

The good news is that you don’t need to know all this to start programming in Elixir and Phoenix. All these concerns can be learned on the fly as they are needed, and you can still be extremely productive.

Phoenix

Phoenix is a web framework written in Elixir.

Phoenix already takes advantage of all the power of Erlang’s processes. Each time you receive an HTML request, a new process is created, which allows thousands of people to access your website simultaneously, without any problem.

Most of the team behind Phoenix comes from the Rails community, so it is only natural that you have borrowed some good ideas:

- Both are MVC frameworks that focus on productivity.

- They provide a default directory structure and generators.

- They use relational databases by default.

- They promote best security practices by default.

- They come equipped with testing tools.

Migrations

This is what a migration looks like in Rails and Phoenix:

class CreateArticles < ActiveRecord::Migration[6.0]

def change

create_table :articles do |t|

t.string :name

t.text :description

t.timestamps

end

end

end

In order to use the migration methods, in Rails it is inherited from ActiveRecord::Migration.

defmodule MyWeb.Repo.Migrations.CreateArticle do

use Ecto.Migration

def change do

create table(:articles) do

add :title, :string

add :description, :string

timestamps

end

end

end

In Phoenix, there is no inheritance, so you write use Ecto.Migration.

Routes

In Rails we have the convention over configuration philosophy. If we adhere to conventions, Rails allows us to write less code.

resources :articles do

resources :comments, only: [:comment]

end

post "login", to: "sessions#login"

root to: "pages#index"

In Elixir we have the philosophy of explicit is better than implicit. In the routes I always have to say explicitly which is the controller that is responsible for each action.

resources "/articles", ArticleController do

resources "/comments", CommentController, only: [:show]

end

post "/login", SessionController, :login

get "/", PageController, :index

We write a little more code, but we have much more flexibility.

To stick to the convention, in Rails we have to use the model name in the plural. And if it is irregular, we have to define the rules of pluralization in Inflector.

Phoenix is much more flexible. We can use the names we want. After all, we will always name them explicitly.

Controllers

There are several points to keep in mind.

class ArticlesController < ApplicationController

def show

@article = Article.find(params[:id])

# render "show.html"

end

end

First, in Rails the show action does not receive any parameters. I have direct access to params, the object request and any instance variable created in a before_action.

defmodule MyWeb.ArticleController do

use MyWeb.Web, :controller

def show(conn, %{"id" => id}) do

article = Blog.get_article!(id)

render(conn, "show.html", article: article)

end

end

In Phoenix I have to pass everything I use as a parameter. The variable conn would be the equivalent of the Rails request object. The show action is a function like any other and the advantage of receiving everything by parameter is that I can test the action in isolation.

The second point is that Rails’ show action implicitly calls render “show.html”. The render copies all controller instance variables to the instance of the view.

In Phoenix, however, you must always write render explicitly. Everything I need to use in the view I have to send it in the render function. That means I can test the views in isolation.

Configuration over convention is a good thing, but there is a point where implicit behavior sacrifices clarity. Phoenix optimizes for clarity.

Views

The views closely resemble Rails views in their syntax:

<h1><%= @article.title %></h1>

<p><%= @article.description %></p>

<%= for comment <- @article.comments do %>

<p class="comment"><%= comment.content %></p>

<% end %>

<%= link "Editar", to: article_path(@conn, :edit, @article) %>

<%= link "Volver", to: article_path(@conn, :index) %>

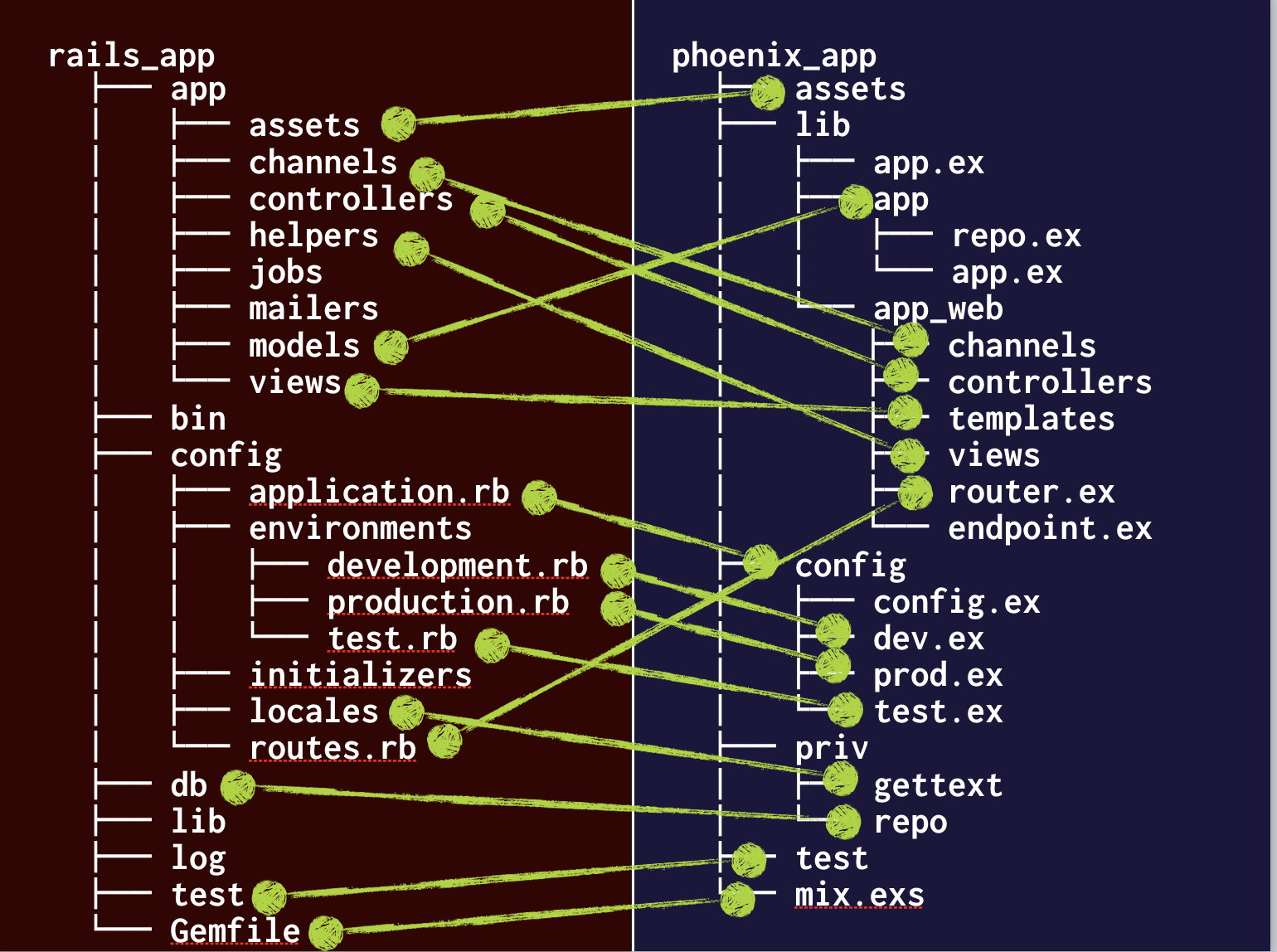

Directory Structure

If you come from the Rails world and want to learn Phoenix, you run with a great advantage. The directory structure created by Phoenix has many points in common with that of Rails

Most of the concepts map one to one.

You can be very productive immediatly.

Channels

Just as Rails has his famous tutorial on how to make a blog in 15 minutes, Phoenix has his tutorial on how to make a chat in real time in 15 minutes. Phoenix has excellent support for websockets.

Websockets allow round-trip communication between client and server, without refreshing the page.

This means that in Phoenix it is very easy to implement

- Real time chats.

- Notifications in real time.

- Collaborative tools with many people connected at the same time

- See who is connected, and when someone connects or disconnects.

- A search engine that communicates to several APIs and returns results as they arrive.

We define a socket, a channel and some Javascript code and we have the chat running. Almost as easily as defining a view and a controller.

Channels are handled with Erlang processes, allowing millions of people to be connected at the same time using a single server computer. Phoenix provides great support for high concurrency totally free.

Performance

Even if you don’t need high concurrency, performance is still a good reason to use Phoenix.

A while ago I made an informal comparison between a basic Phoenix and Rails application . And the Phoenix application, with access to databases running locally, was around 7 times faster.

And without access to databases, the difference was even greater. In Phoenix it is common to see reports like this:

Sent 200 in 517µs

That symbol means microseconds. That is half a millisecond.

Performance is very important, especially on the web.

It is shown that if a page takes more than 100 milliseconds to load, it negatively affects people’s attention. There are studies of how companies multiplied their conversions by reducing the response time by a few milliseconds.

And it is also important for the programmer during development. We have the same attention problems.

It never happened to you to wait so long for something to happen to not remember what you were doing?

In Phoenix, running the server is almost instantaneous. The navigation is immediate, it feels like it is a static web page. The tests take seconds instead of minutes. This positively impacts our attention and our programming experience.

And the performance is not only better in speed, but also in memory.

Bleacher Report made the transition from Rails to Elixir, and they went from using 150 servers to using 5 servers, and at the same time they improved their response times for their 200 million daily push notifications.

I think one of the reasons we make small websites is because we don’t dare to do bigger things.

When you have all the power of the Erlang virtual machine in your hands, you are encouraged to challenges that you did not think were within your reach.

Elixir makes historically complicated problems easy, and since these solutions are now at your fingertips, you are encouraged to offer your customers much more exciting functionalities.

Phoenix has the ability to give a competitive advantage to your customers, and also to you as a company and to you as programmers.

The challenges of the modern web

The web is evolving. The modern web is highly connected and needs real-time systems. It requires including connected devices such as tables, phones and watches.

You need highly available, scalable, fault tolerant and distributed systems. You need systems that can take full advantage of the computer’s processing capacity.

Erlang and Elixir were created to solve these types of problems. Phoenix was built from day one to meet the challenges of the modern web.

The technologies are advancing very quickly and in our field it is important to be able to adapt to the new requirements. We simply have to overcome fears and do it.

Do we dare to face the challenges of the new web?